Basic QC Practices

A Global Survey of Veterinary Laboratory QC Practices

In 2017, as part of the ESVCP meeting in London, we conducted and presented a small survey of veterinary laboratories and their QC practices. What do their results tell us about the state of quality control? Are they doing better QC than "human labs"?

The Great Global VET QC Survey: Results from Veterinary Laboratories

December 2017

Sten Westgard, MS

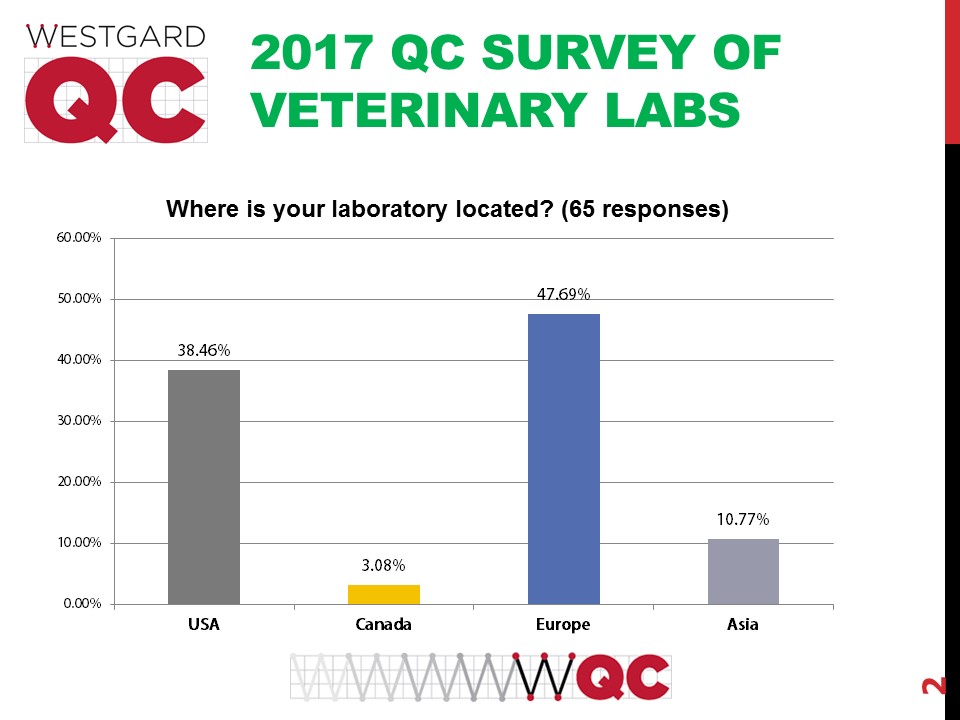

After looking at the breakdown of the Great Global QC Survey results within the US and outside the US, we decided to also look at veterinary laboratories. Over the course of a few months, we gathered more than 60 responses.

We presented at the Imperial College of London.

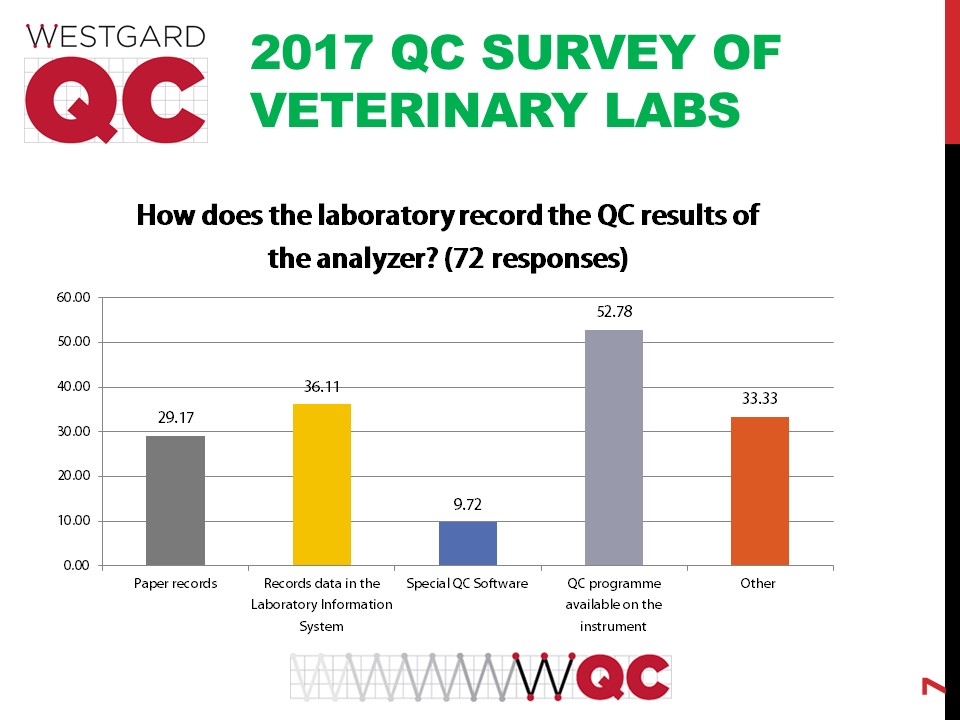

A majority of the labs rely on the instrument-based QC software. But also nearly a third of labs still do QC on paper. The state of informatics in veterinary labs is probably one of the least developed.

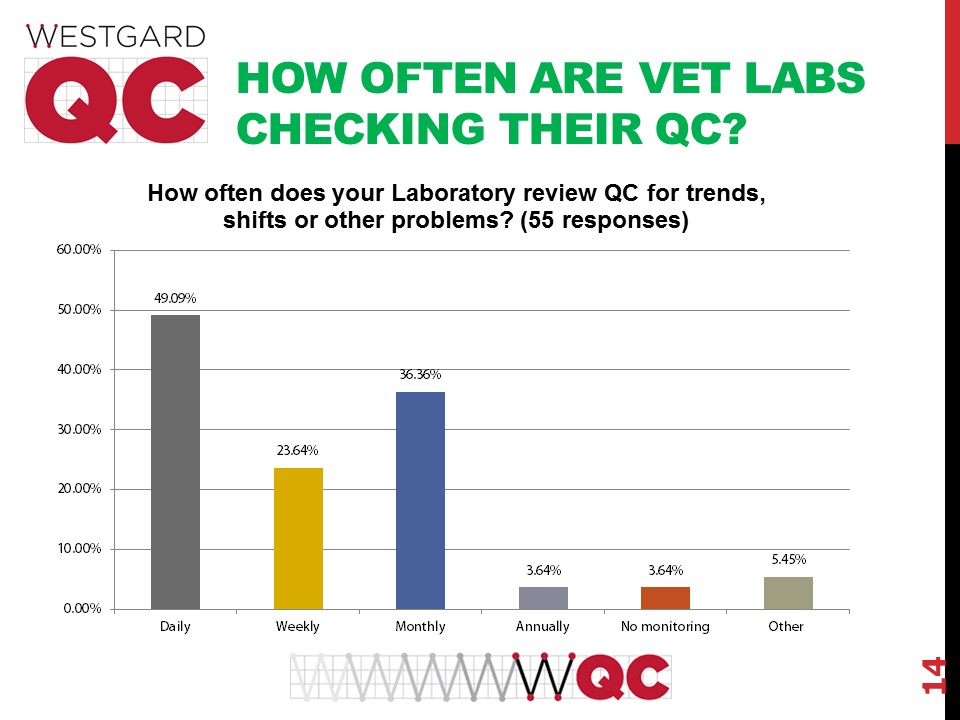

The survey asked how often veterinary laboratories are checking their QC.

In some ways this begins to show the difference between vet labs and "human labs." The vet labs may only be adhering to a nominary QC regimen, not one as stringent as is implemented for "human labs."

This survey was also different than our earlier surveys of QC practices, in that there were questions specifically about chemistry, hematology and endocrine testing.

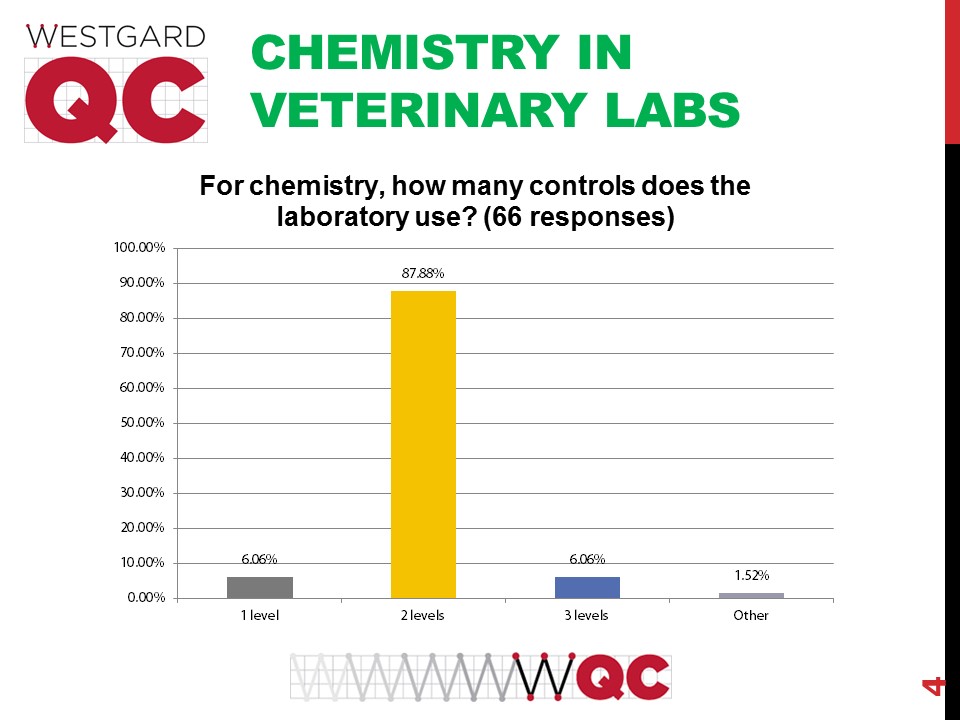

The uniformity of practice here is impressive: 2 controls being used in chemistry is the dominant standard.

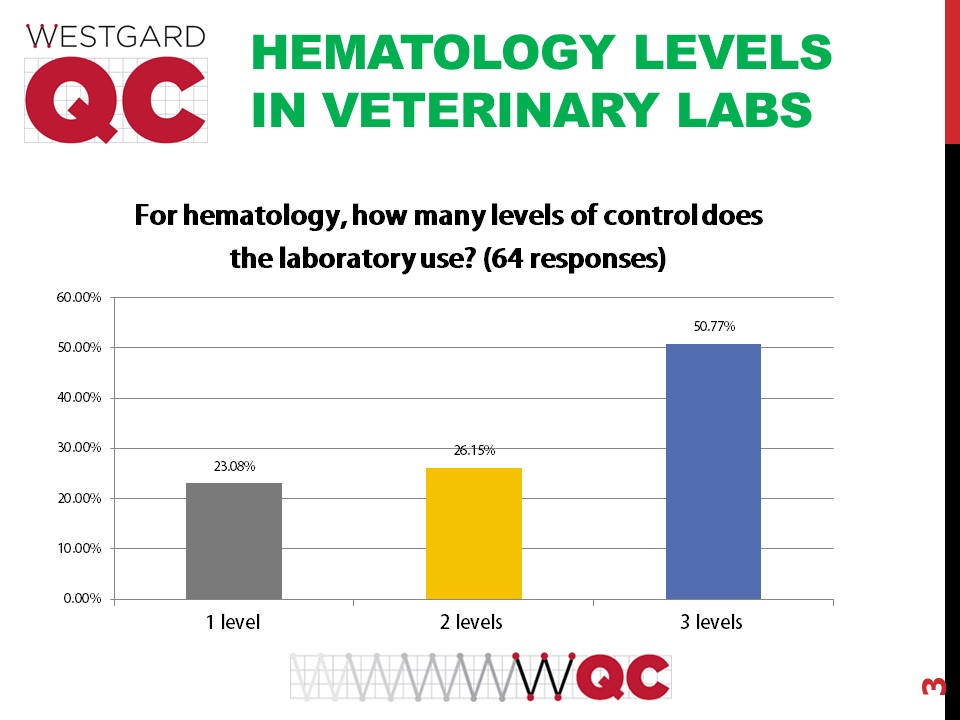

In hematology, there is much more considerable variation. A majority are using 3 levels, but nearly a quarter are using 2 levels of QC, and some are only running 1 level, a practice that would be frowned upon in traditional human laboratories.

For endocrine testing there is no majority practice of laboratories, but the most common practice is to run 2 levels.

Again, the standard of practice is running QC for chemistry just once per day.

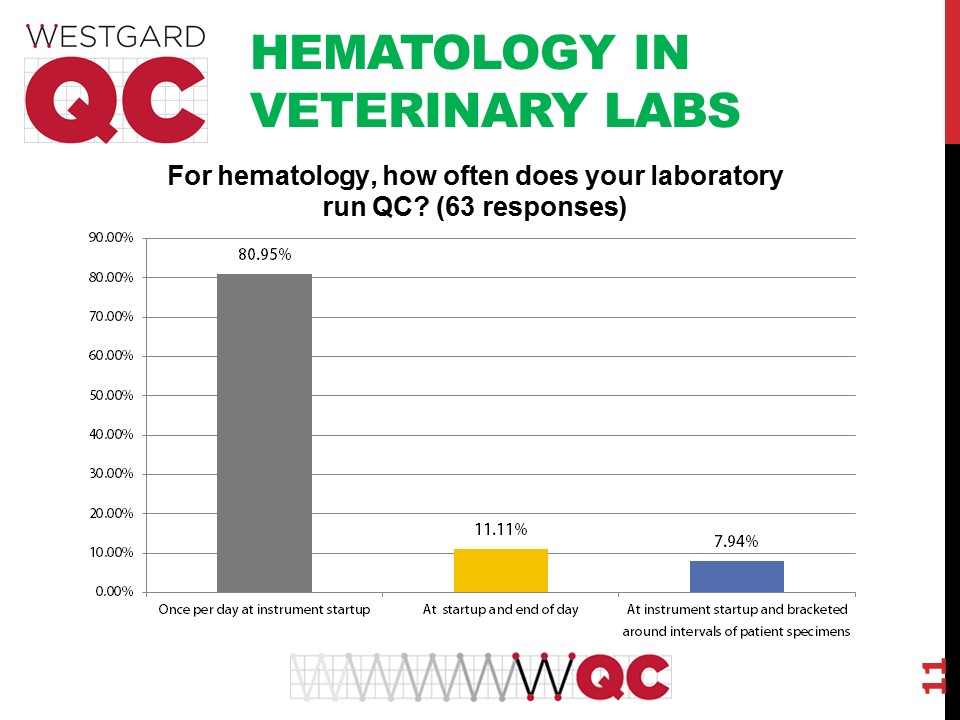

Hematology is also being run only once a day. The usual practice in human laboratories is several times per day.

Endocrinology, as with the other areas, is only being run once a day.

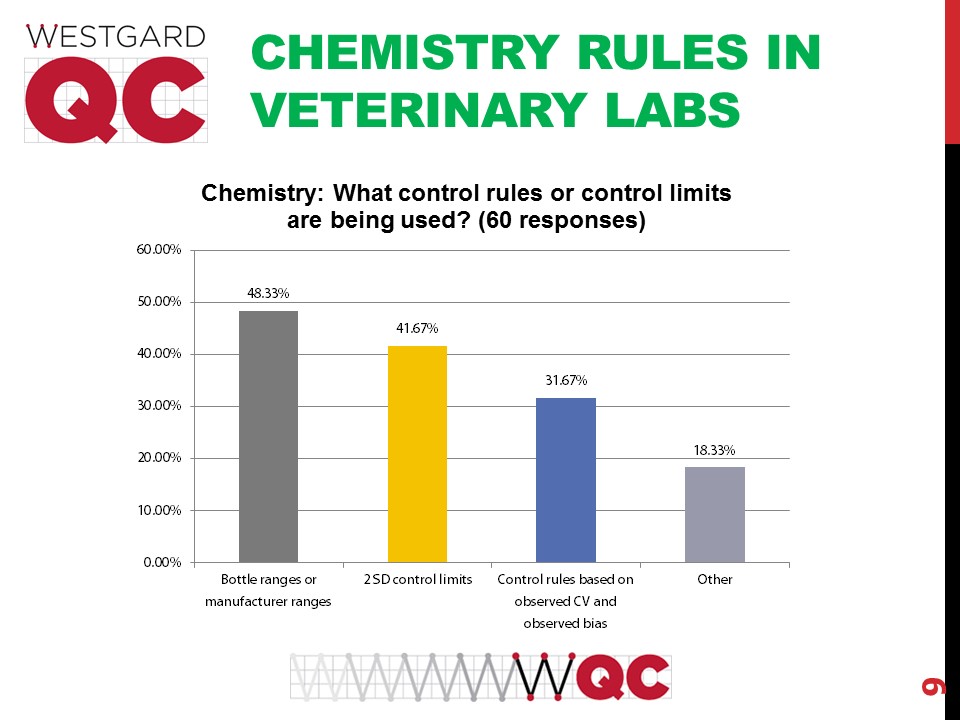

The QC practices for chemistry used in veterinary labs are not the most modern and have some serious drawbacks. Using the manufacturer or bottle ranges is what we call "blind man" QC - limits set too wide for useful error detection. The use of 2 SD limits is antiquated and will generate too many false rejections. Less than a third of labs are doing the QC that is most appropriate, fitting the QC to the performance observed of the method.

In hematology, the practices are even worse. A majority of labs use the manufacturer or bottle ranges, making themselves even more blind. Even more labs also use the 2 SD limits. Fewer labs do the right QC based on method performance.

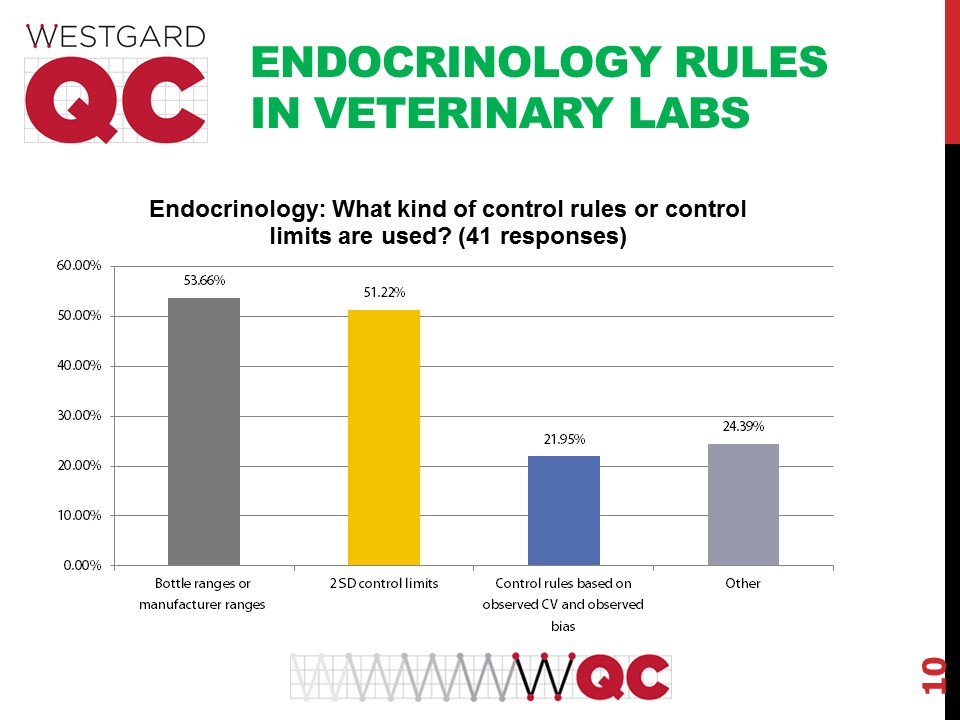

For endocrinology the practices seem worst of all, a majority of labs reporting that they use manufacturer ranges and 2 SD limits. A "2 SD" of a manufacturer's SD will usually generate very wide limits that give the illusion of everything being "in control" while the reality is that there may be out-of-control events that go undetected.

Once an out-of=-control event occurs, thankfully a majority of the labs are responding with an appropriate troubleshooting protocol. However, the next most common response is rather detrimental, a repeat of the control to try and get the result back "in." As many of you know, we call that Gambler QC.

A majority of veterinary labs don't calculate measurement uncertainty.

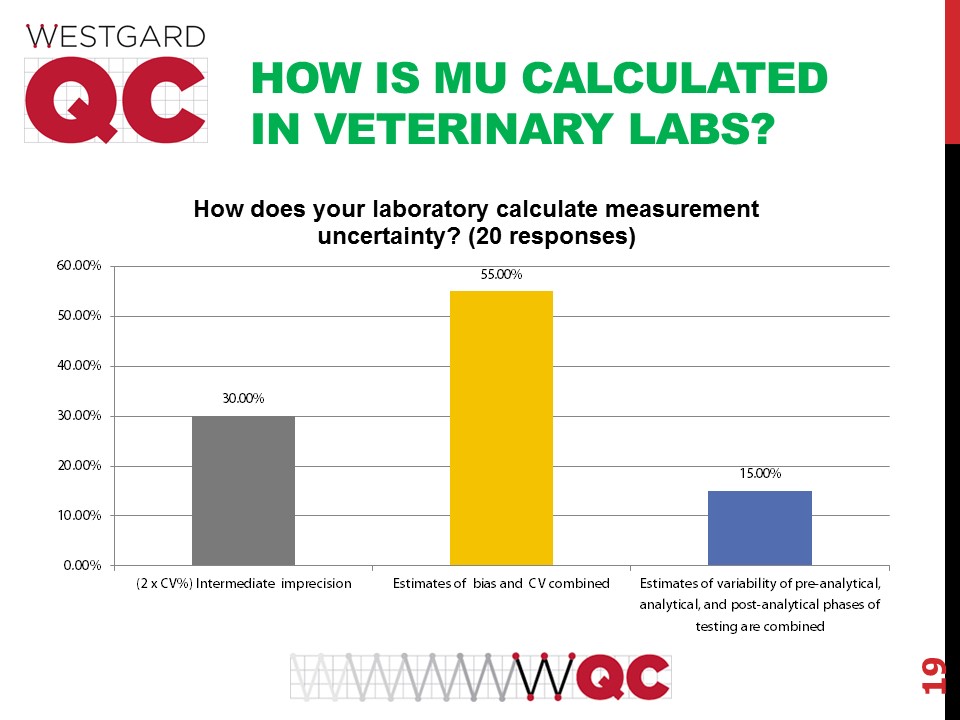

Of the labs that do calculate measurement uncertainty, there is no standardization about how to calculate MU. About a third of vet labs just multiply their SD by 2. More labs combine bias and CV, which by many metrologists is a violation of the very fundamental tenets of MU. Still another portion attempt to combine estimates of uncertainty of not only the analytical phase but also pre-analytical and post-analytical phases.

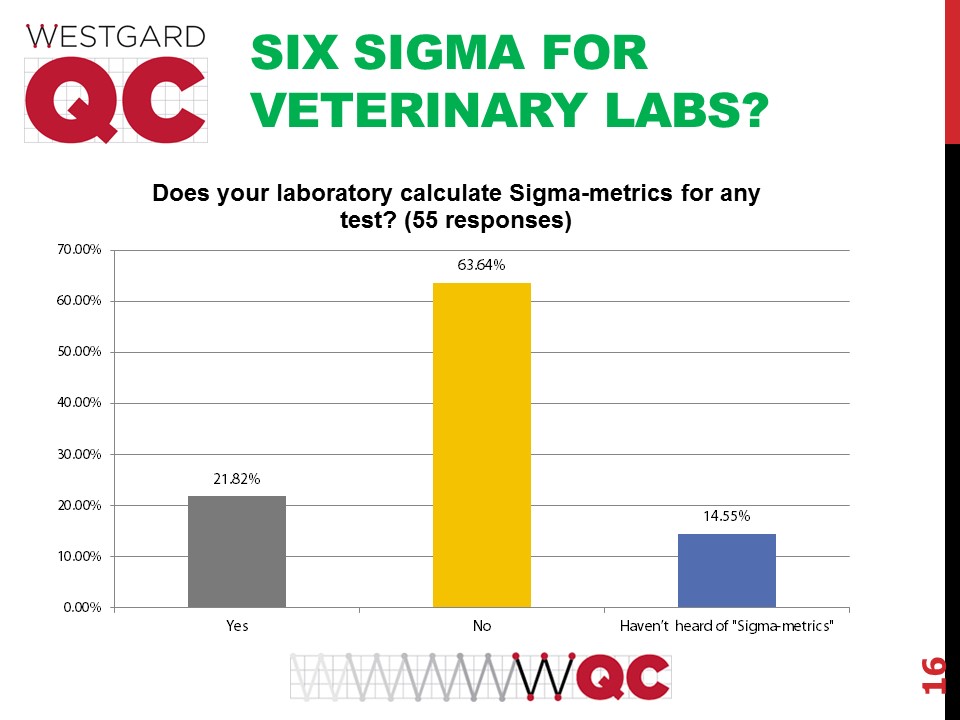

A smaller portion of veterinary laboratories use Six Sigma and Sigma-metrics in their operations than use measurement uncertainty.

For those labs that do use Sigma-metrics, they put those metrics to many purposes. The majority use Sigma-metrics to redesign how they implement their quality control procedures. The next most popular use is to identify which methods need to be improved. Few labs use Sigma-metrics to help them choose new methods and instruments, which is actually where sigma-metrics can have their most powerful impact on a laboratory. If you can select a Six Sigma assay to bring into your laboratory, you have the opportunity to make efficiencies, reduce workload, and increase confidence in the clinical decision making.

Conclusion

There are some encouraging findings in this survey, but many practices in veterinary laboratories are not as sophisticated as what we see in "human labs". There are more detrimental QC habits, like using wide ranges and 2 SD limits. These practices are still quite common in "human labs" but they seem to be even more prevalent in veterinary labs. What is striking is that the literature for veterinary laboratory medicine is sometimes much more advanced than what we see in the "human lab" medicine journals - for instance, there are multiple papers where the technique of "repeat patient QC" has been studied, but no similar studies have been conducted in human laboratories. So there is even a wider distance between the literature and the practice of vet labs.

But the core finding is that vet labs have the same shortcomings as human labs. That is not fate, however, because there is always the ability to change those practices in the future.